Find the complete text of the Analects of Confucius.

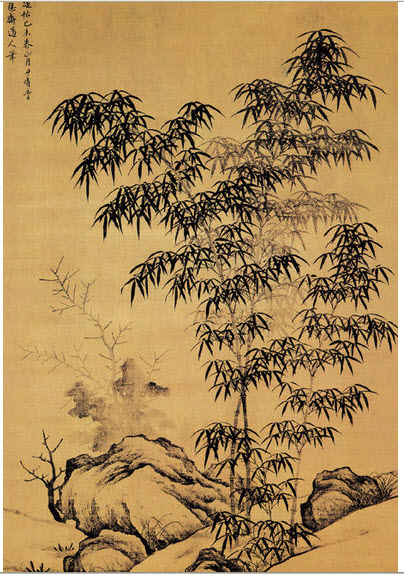

Giant Bamboos and Stones, Li Kan, Yuan Dynasty, China, Nanjing Museum

13th century, Yuan DynastyBOOK XIX

Teachings of Various Chief Disciples

"The learned official," said Tsz-chang, "who when he sees danger ahead will risk his very life, who when he sees a chance of success is mindful of what is just and proper, who in his religious acts is mindful of the duty of reverence, and when in mourning thinks of his loss, is indeed a fit and proper person for his place."

Again he said, "If a person hold to virtue but never advance in it, and if he have faith in right principles and do not build himself up in them, how can he be regarded either as having such, or as being without them?"

Tsz-hiá's disciples asked Tsz-chang his views about intercourse with others. "What says your Master?" he rejoined. "He says," they replied, "'Associate with those who are qualified, and repel from you such as are not,'" Tsz-chang then said, "That is different from what I have learnt. A superior man esteems the worthy and wise, and bears with all. He makes much of the good and capable, and pities the incapable. Am I eminently worthy and wise?—who is there then among men whom I will not bear with? Am I not worthy and wise?—others will be minded to repel me: I have nothing to do with repelling them."

Sayings of Tsz-hiá:—

"Even in inferior pursuits there must be something worthy of contemplation, but if carried to an extreme there is danger of fanaticism; hence the superior man does not engage in them.

"The student who daily recognizes how much he yet lacks, and as the months pass forgets not what he has succeeded in learning, may undoubtedly be called a lover of learning.

"Wide research and steadfast purpose, eager questioning and close reflection—all this tends to humanize a man.

"As workmen spend their time in their workshops for the perfecting of their work, so superior men apply their minds to study in order to make themselves thoroughly conversant with their subjects.

"When an inferior man does a wrong thing, he is sure to gloss it over.

"The superior man is seen in three different aspects:—look at him from a distance, he is imposing in appearance; approach him, he is gentle and warm-hearted; hear him speak, he is acute and strict.

"Let such a man have the people's confidence, and he will get much work out of them; so long, however, as he does not possess their confidence they will regard him as grinding them down.

"When confidence is reposed in him, he may then with impunity administer reproof; so long as it is not, he will be regarded as a detractor.

"Where there is no over-stepping of barriers in the practice of the higher virtues, there may be freedom to pass in and out in the practice of the lower ones."

Tsz-yu had said, "The pupils in the school of Tsz-hiá are good enough at such things as sprinkling and scrubbing floors, answering calls and replying to questions from superiors, and advancing and retiring to and from such; but these things are only offshoots—as to the root of things they are nowhere. What is the use of all that?"

When this came to the ears of Tsz-hiá, he said, "Ah! there he is mistaken. What does a master, in his methods of teaching, consider first in his precepts? And what does he account next, as that about which he may be indifferent? It is like as in the study of plants—classification by differentiae. How may a master play fast and loose in his methods of instruction? Would they not indeed be sages, who could take in at once the first principles and the final developments of things?"

Further observations of Tsz-hiá:—

"In the public service devote what energy and time remain to study.

After study devote what energy and time remain to the public service.

"As to the duties of mourning, let them cease when the grief is past.

"My friend Tsz-chang, although he has the ability to tackle hard things, has not yet the virtue of philanthropy."

The learned Tsang observed, "How loftily Tsz-chang bears himself!

Difficult indeed along with him to practise philanthropy!"

Again he said, "I have heard this said by the Master, that 'though men may not exert themselves to the utmost in other duties, yet surely in the duty of mourning for their parents they will do so!'"

Again, "This also I have heard said by the Master: 'The filial piety of Mang Chwang in other respects might be equalled, but as manifested in his making no changes among his father's ministers, nor in his father's mode of government—that aspect of it could not easily be equalled.'"

Yang Fu, having been made senior Criminal Judge by the Chief of the Mang clan, consulted with the learned Tsang. The latter advised him as follows: "For a long time the Chiefs have failed in their government, and the people have become unsettled. When you arrive at the facts of their cases, do not rejoice at your success in that, but rather be sorry for them, and have pity upon them."

Tsz-kung once observed, "We speak of 'the iniquity of Cháu'—but 'twas not so great as this. And so it is that the superior man is averse from settling in this sink, into which everything runs that is foul in the empire."

Again he said, "Faults in a superior man are like eclipses of the sun or moon: when he is guilty of a trespass men all see it; and when he is himself again, all look up to him."

Kung-sun Ch'an of Wei inquired of Tsz-kung how Confucius acquired his learning.

Tsz-kung replied, "The teachings of Wan and Wu have not yet fallen to the ground. They exist in men. Worthy and wise men have the more important of these stored up in their minds; and others, who are not such, store up the less important of them; and as no one is thus without the teachings of Wan and Wu, how should our Master not have learned? And moreover what permanent preceptor could he have?"

Shuh-sun Wu-shuh, addressing the high officials at the Court, remarked that Tsz-kung was a greater worthy than Confucius.

Tsz-fuh King-pih went and informed Tsz-kung of this remark.

Tsz-kung said, "Take by way of comparison the walls outside our houses. My wall is shoulder-high, and you may look over it and see what the house and its contents are worth. My Master's wall is tens of feet high, and unless you should effect an entrance by the door, you would fail to behold the beauty of the ancestral hall and the rich array of all its officers. And they who effect an entrance by the door, methinks, are few! Was it not, however, just like him—that remark of the Chief?"

Shuh-sun Wu-shuh had been casting a slur on the character of Confucius.

"No use doing that," said Tsz-kung; "he is irreproachable. The wisdom and worth of other men are little hills and mounds of earth: traversible. He is the sun, or the moon, impossible to reach and pass. And what harm, I ask, can a man do to the sun or the moon, by wishing to intercept himself from either? It all shows that he knows not how to gauge capacity."

Tsz-k'in, addressing Tsz-kung, said, "You depreciate yourself. Confucius is surely not a greater worthy than yourself."

Tsz-kung replied, "In the use of words one ought never to be incautious; because a gentleman for one single utterance of his is apt to be considered a wise man, and for a single utterance may be accounted unwise. No more might one think of attaining to the Master's perfections than think of going upstairs to Heaven! Were it ever his fortune to be at the head of the government of a country, then that which is spoken of as 'establishing the country' would be establishment indeed; he would be its guide and it would follow him, he would tranquillize it and it would render its willing homage: he would give forward impulses to it to which it would harmoniously respond. In his life he would be its glory, at his death there would be great lamentation. How indeed could such as he be equalled?"

|

|